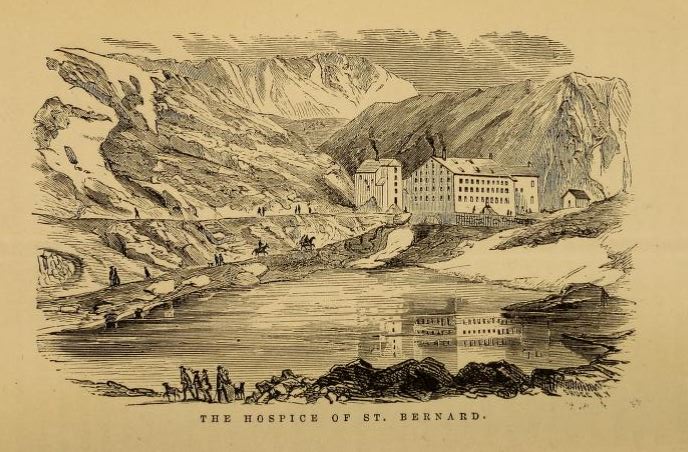

The St Bernard Morgue

As we have previously observed in some of my more gruesome posts, death tourism is nothing new. Today, in this first of an occasional series of “Little Visits to the Great Morgues of Europe,” we pay a frigid visit to the morgue at the Great St Bernard Hospice in the Pennine Alps.

The St Bernard Morgue.

The great curiosity of the Monastery of the Mount St. Bernard is the morgue. If the day is a little warm the brother who attends to visitors hesitates a bit before opening the door of the wooden house just outside the chief building. He first drives away the dogs, who come prowling about, snuffing the air suspiciously, and has them shut in their room opposite the huge refectory. Then he marshals the little company of international tourists in line before the mysterious door, and opens the chamber of horrors. The keen mountain air rushes in, and presently you are conscious of a faint, sickly odor—not strong enough to be repulsive, but eminently suggestive of death. Then, as you stand there, peering with strained eyeballs into the darkness, you become vaguely conscious that a face is looking at you. I defy any one who is possessed of the smallest grain of imagination to see that mysterious face growing slowly out of the obscurity without a sudden sinking of the heart and a chill which no effort of the will can suppress. It is the face of a woman — and yet of a ghost; a kind of corporeal presence divested of life, and yet so horribly like life, that you are almost afraid that the bony and skinny frame to which it belongs will arise and stretch out its dreadful arms, and drag you down into the depths which you so instinctively shun. The good brother does not say anything; he watches the effect of this curious spectacle upon you. Pretty soon you can discern that the face belongs to the body of a woman—and that this woman is clasping to her breast the form of a tiny babe. The mother is seated on the ground, and appears to be dazed by the light pouring down into her darksome habitation. But, oh! the horror of her face! Here is death without decay; here, in this wondrous air, on this pass more than eight thousand feet above the sea level, putrefaction is unknown; and bodies found in the snows in winter — or after the white shroud has melted away from the bosom of nature in the spring — are preserved entire so long as the monks care to keep them. The grimness of the spectacle is enhanced by the fact that nearly every body found is contorted, twisted, strained and knotted in fantastic shapes. Now and then one which bears all the appearance of tranquil sleep is brought in; but in most cases there are indications that man and woman, in their battle with Nature, fought hard and desperately, and refused to be overcome until every particle of force was exhausted. The brethren gather up the bodies with tender care and place them in the dead-house in the usually vain hope that some relatives may come to recognize them. Where is the father of the child which this strange spectral mother clasps in her arms? What was the history of the woman who had thus wandered in the wild winter from the Rhone valley toward the kinder and warmer Italian slopes? Perhaps her husband was with her — and perhaps his body now lies at the bottom of some precipice where even the “pious monks of St. Bernard” cannot find him—or perhaps he is here, in the dead-house; perhaps that prostrate body, seeming to grovel on the rocky floor, is his. The peasants rarely carry any paper which can completely identify them, and sometimes the unfortunates found dead in the pass here led such wandering lives — going to Switzerland for harvest work in the summer, and to Italy when the winter nips them—that their passports even give no clew to their birth-place or native villages.—From a Letter to the Boston Journal.

The Western Lancet, Volume 12, Eustace Trenor, Heman P. Babock, 1883: p. 43

The Hospice is, of course, famous for its breed of recue dog, the St. Bernard, the ones shooed away from the door of the morgue in a minor, but telling detail.

I’d like to say that it seems incredible to us today that anyone would visit a morgue as a form of entertainment, but death-dealing video games and the 24-hour news cycle, with its Warning: Graphic Content photos on internet news sources would suggest that those who enjoy viewing corpses are now doing it from the comfort of their own homes. A kind of slaycation.

Other accounts of the St Bernard Hospice morgue? Drift over to chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

See these posts on the charnel pits of Palermo and visiting Paris during cholera epidemics. A lengthy article on the New York Morgue in 1868 is found in The Victorian Book of the Dead.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.