The Word Made Flesh At Burgos

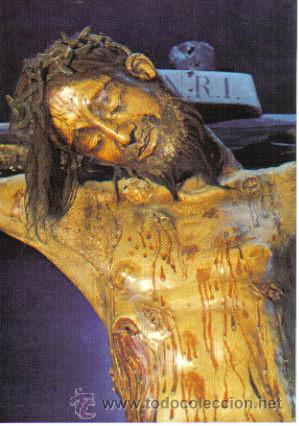

The Word Made Flesh At Burgos: A close-up of the Christ of Burgos

I psychically sense that my readers are tiring of stories of premonition and prophecy, so let us turn, in this Holy Week, to a unique and macabre religious icon, The Christ of Burgos.

One of the towers of Burgos Cathedral

Catedral de Santa María de Burgos is a massive structure in a thorny Gothic style, peculiar to the Iberian peninsula. It is perhaps best known as the burial place of “El Cid.” It is also home to a rather terrifying automaton called Papamoscas (Flycatcher), which rings a bell on the hour and opens and closes its grinning mouth the same number of times as the hour. The current version is an 18th-century replacement for the original 16th-century one. There are a few videos of Papamoscas in action (none of them terribly good) on Youtube.

“The Flycatcher” automaton at Burgos

This Mephistophelean automaton is only a prelude to the ghastly figure found in its own special chapel: the 14th-century Cristo de Burgos. Some say that the figure of the crucified Christ is made from human skin over an armature. Others claim that it is a stuffed or mummified human corpse. Current literature maintains that the corpus is made of wood, human hair and cowhide filled with wool and realistically painted.

Here is an early 20th-century description:

We shall see presently that the Cristo of Burgos was for some time in possession of Augustines. In ‘The Romance of Religion,’ by Olive and Herbert Vivian (1902), we are told of it:—

“This image is famed all over Spain for the miracles it has wrought, and the priests who have charge of the chapel constantly declare that they have seen it move its head and arms. The legend says that a merchant returning from Flanders found it when sailing alone in the Bay of Biscay. It was first preserved in the Augustine Monastery, and was so much coveted by other monks that twice it was stolen. Each time, however, the image refused to stay in its new home, and found its way back unaided to the Augustines. [In the usual way of mysterious holy images.]

In former days it was concealed behind three curtains of silk covered with gold and pearl embroideries, which would open slowly and solemnly to the sound of bells on great ceremonies. The weariness and deathlike appearance of the figure are unutterable. To give an additional touch of realism, the wooden body is covered with human skin, which, in the course of centuries, has become all cracked and scarred. For a long time this was disbelieved, but a French writer [Theophile Gautier? See below] obtained permission to examine the figure closely, and confirmed the truth of it. He noticed, too, that on the hands and feet the nails are attached to the skin. [Damning, if true] The head is made of wood, but the hair and beard are real. The people of Burgos say that the hair has not ceased to grow, and moreover declare that the image sweats every Friday.”—Pp. 109-11.

Who was the investigating Frenchman? Not very long ago I was assured by a sacristan of reverent bearing at Burgos Cathedral that the skin was not human, but bovine. He believed in the miraculous power of the Cristo.

St. Swithin

Notes & Queries, William Wise 24 December 1904: p. 511

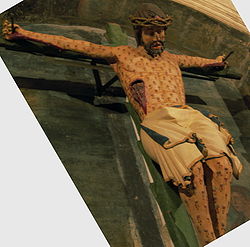

The embroidered skirt on the image is a popular (although not exclusively) Hispanic tradition. There is a famous 17th-century crucifix in Cuzco, Peru called “The Lord of the Earthquakes,” that I think may have been modeled on the Burgos figure. It, too, wears the longer vestment, meant to suggest Christ’s royal lineage and to honor the sacred figure.

Cult images reverenced throughout the year in Spanish cathedrals and carried through the streets during Holy Week are often clothed in real garments. They also may have glass eyes and are painted hyper-realistically to depict bruised and scourged skin and the other wounds of the Passion. The Virgin of Sorrows is shown with real swords piercing her bosom and crystal tears trickling down her cheeks. These theatrical pieties are akin to the impetus that gave movement and facial expression to Boxley Abbey’s Rood of Grace by means of strings and wires.

There is also a tradition of articulated images of the Christ to be used in the rituals of Holy Week, the Deposition from the Cross, and the Entombment of Christ, as we are told in this passage from this site discussing the origins and significance of the Burgos image.

And, as I am always on the lookout for patterns, I was also reminded of the legendary charge of El Cid’s armored corpse at the Siege of Valencia. From El Cid to the Flycatcher and the Cristo: Burgos has a minor theme of animated–and to modern eyes, gruesome figures.

Theophile Gautier, possibly the Frenchman referenced in the Notes & Queries entry above, suggests aptly that the Spanish are addicted to a “terrible love of realism” in their art. Hence this tortured Christ—truly a Man of Sorrows.

The celebrated Christ, so revered at Burgos that no one is allowed to see it unless the candles are lighted, is a striking example of this strange taste: it is neither of stone, nor painted wood, it is made of human skin (so the monks say), stuffed with much art and care. The hair is real hair, the eyes have eye-lashes, the thorns of the crown are real thorns, and no detail has been forgotten. Nothing can be more lugubrious and disquieting than this attenuated, crucified phantom with its human appearance and deathlike stillness; the faded and brownish-yellow skin is streaked with long streams of blood, so well imitated that they seem to trickle. It requires no great effort of imagination to give credence to the legend that it bleeds every Friday.

Voyage en Espagne, Theophile Gautier, 1865

Given the incidents of bleeding and weeping Madonna statues and prints that continue to the present day, it is impossible to say if the bleeding was an optical illusion, a genuine miracle, or a priestly imposture. The theatrical curtain openings and the candlelight requirement suggest that the third option is perhaps the most plausible one.

The image has been duplicated multiple times, including this version from the Phillipines.

This version, from another Burgos church, has a stylized pattern on the skin to suggest scourging.

Other articulated or ultra-realistic religious icons? Any others reputed to be made of human skin? And does anyone know if DNA or other conclusive testing has actually been done on this image? Chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

See also this post on a moving crucifix from the Great War.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead. And visit her newest blog, The Victorian Book of the Dead.