Banshee in a Red Shirt: A Puzzle

While working on The Victorian Book of the Dead, I ran across this story told by a man who had once helped move bodies from an old Kentucky cemetery. I read it once, twice, half a dozen times. I looked for other versions in other newspapers because it looked like something–a punch line or an explanation–must be have been left out. I was bitterly disappointed: banshee stories–whether knocking or screaming–are so rare in the United States that I was happy to find a new one. Yet since I felt the tale was incomplete, I couldn’t use it in the new book. See what you think–is something missing?

GRAVEYARD SPIRITS

Reminiscence of Former Maysvillian Who is Now Visiting here.

Colonel William L.H. Owens of Louisville, now on a visit in this city, dropped in on The Ledger for a social call yesterday, during which he put the following story into type—

“I wish to relate an experience in my life, the memory of which has lingered with me for over half a century. It happened at the old graveyard, which was located just where the depot now stands at the head of Third street. The graveyard was being wrecked, that the railroad company might have the use of the ground. At this time “spirit rapping” was a mysterious novelty, as well as a terror to the small boy—which terror was equal to “a snake in the grass” sensation. Well, there was no help for it; the bodies had to be removed; so I constituted myself High Resurrectionist—or Superintendent. Many gruesome sights greeting my eyes, and I saw unearthed the bodies of many persons whom I had seen in life walking the streets of Maysville. But this narrative deals with “spirit-manifestations.” The Eastern end of the graveyard, where the “potters” were buried, was composed of a clay that held water. There was Billy Tolle, the foreman, and under him John Knox and other grave-men whom I knew. They began digging into a grave, and soon the hard ground turned to hard clay. But the coffin-boards were soon removed, and the head of the coffin slightly raised by John Knox, who was in the grave, a lifting-rope placed in properly, and the work began—slowly, very slowly, a little progress made, when the men took a little rest, and as the coffin settled back into the miry clay there was distinctly heard a knock-knocking, a knock-knocking coming from the inside of the coffin. The men were affrighted, dropped the rope and John Knox clambered out of the grave, and for a while the knocking continued, growing fainter and fainter, till, with a seeming sigh, it ceased. Meanwhile the men stood in a group, looking down into the open grave. Each had an awe-stricken look on his face, the left corner of the mouth showing the distress of amazement. I was conscious of the brightness of the sun and the blueness of the sky; but for my escape I relied mainly on the fact that in the Southeast corner of the graveyard there was a gorge under the fence, through which I could drop, descend to the valley, and soon reach Limestone Creek, though which a disembodied spirit might not pass. As for the men, they said not a word, as they stood, their elbows resting on their pick-handles, with the palms of their hands supporting their chins, their eyes fixed on the hole in the ground.”

“I wonder, dear reader, what you would have done, had you been in the place of the little boy, who, with beating heart and wide-open eyes, stood watching the men and the unanswering grave! Unless the mystery were solved, the stars would shine in his eyes all night, so he was glad when he saw his friend Billie Tolle, the boss, coming forward. ‘How now, what is the trouble?’ ‘It is the Banshee, sure,’ said John Knox. ‘Banshee?” queried the boss. “Banshee in the coffin, there.’ ‘Nonsense; what is the Banshee?’ ‘In my country it is the Banshee that comes to warn you of danger or trouble.’ ‘Oh, there’s no Banshee in that coffin; get down into the grave and lift the coffin. Neither of the men would venture, so the boss got down himself, and adjusted the ropes. Then came the tug of war; slowly came the coffin to the surface, while the knocking kept up with distressing vehemence. At last, the coffin was placed on the bier, with the water streaming out, and the knock-knocking gradually ceased. Mr. Tolle then took a spade and, reverently, as I thought, lifted the lid of the coffin, disclosing the form of a man, which had on the head a black felt hat, and clothed with a red shirt belted into his pants, which were stuck into his boots. And the mystery was made plain.”

Public Ledger [Maysville KY] 31 July 1909: p. 2

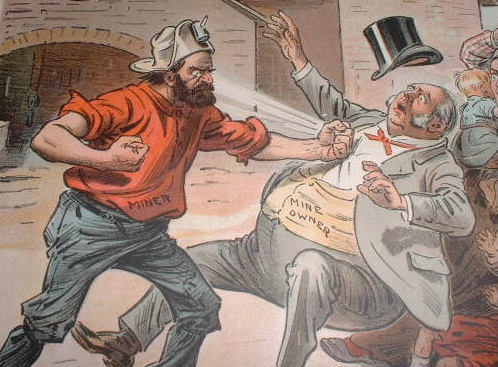

What? Made plain how? It seems as if there should have been a line or a paragraph about an animal jumping out of the coffin, just to finish the thing off. I showed it to my editor who remarked that the body’s costume must be significant. I agreed, but couldn’t quite put my finger on it. Then, while looking into the Coal Strike of 1902, I found this cartoon and realized that it seems as if the corpse was that of a stereotypical miner. But would this have been realized by the newspaper’s readers? And does the fact that the body seems to have been well-preserved matter to the story?

A miner punches the mine owners: a cartoon about the Great Coal Strike of 1902.

What do you think–is this a plausible identification of the body’s occupation? If so, the knocking might make a certain amount of sense: Some miners (usually classed as “superstitious”) believed in Knockers–the spirits of the mine. Sometimes these spirits revealed a rich vein of ore; more often they were omens of death. So, I suppose in a sense a knocking miner could have been conflated with a knocking banshee…. Yet it really seems an unsatisfactory explanation and I’m sitting here gnawing my lip in an agony of doubt.

Knock-knock. Who’s there? Answers, please, to chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Dan Schneider had an intriguing–and, if we assume the corpse is a miner–plausible suggestion:

“When miners become trapped in a cave in they knock on the walls so outside help can determine their location. So a dead miner not realizing he’s dead and buried would knock on his coffin lid until he was “rescued”. I think the article was meant as a joke\humor.

Chris Woodyard is the author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com. Join her on FB at Haunted Ohio by Chris Woodyard or The Victorian Book of the Dead.